Developing a product from scratch takes a lot of compatibility code, code maintenance, cross-browser testing and user testing. Building a WordPress theme/plugin bundle requires a lot of frontend/backend compatibility code starting with PHP/Node.js, the actual WordPress CMS (pre- and post-5.0), all the way to Intersection Observer and Fetch APIs, Promises and CSS variables.

As a quick example, Intersection information is needed for many reasons, such as:

- Lazy-loading of images or other content as a page is scrolled.

- Implementing “infinite scrolling” websites, where more and more content is loaded and rendered as you scroll, so that the user doesn’t have to flip through pages.

- Reporting of visibility of advertisements in order to calculate ad revenues.

- Deciding whether to perform tasks or animation processes based on whether the user will see the result.

The Fetch API provides an interface for fetching resources (including across the network), similar to XMLHttpRequest, but with a more powerful and flexible feature set.

Let’s say that the server software is already up-to-date, PHP 7.2 in our case (with 7.3 round around the corner), backed by Nginx, so the next compatibility decision is JavaScript. I want to use the latest ES6, Intersection Observer and Fetch features, template literals and more, while avoiding any dependency hell caused by npm.

For CSS, I want to use Flex, Grid, and CSS variables. Oh, and object-fit. And max-content, min-content and fit-content. And no CSS preprocessors, as nothing they do can’t be reproduced in CSS.

While Edge is, somewhat, on top of things, IE doesn’t even try. So, what am I supposed to do?

Know Your Audience

The first step is to assess the audience. Is it worth dropping that user segment? Do they bring any benefit to our product, and is the respective user segment worth maintaining all the compatibility code we have? We decided that, no, the extra time and maintenance were not justified.

After careful measurements and analysis of user technology, browsers and devices, we started removing things gradually.

Implementation

As a first example, we use lazy loading. Until Chrome and Firefox will implement the new native lazy loading parameters, we are using a library called yall.js (Yet Another Lazy Loader), implementing all the best practices based on IntersectionObserver. This feature is not available in IE, so yall.js version 2 uses compatibility code, detecting user scrolling. This is rather expensive and delays user interaction time.

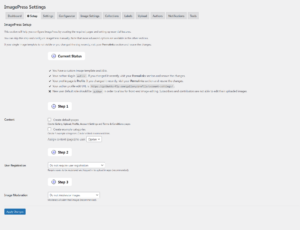

yall.js version 3 removes this compatibility and makes the codebase smaller. Instead, they introduce a polyfill, which we disabled by default, but allowed site administrators to enable, based on their audience.

As a second example, we use colour customisation and all the user settings are read on every page load. That’s a lot of inline style. After we switched to CSS variables, all the inline style (sometimes up to 500 lines) disappeared. All CSS variables are written as data attributes and cached. Yay for blazing speed!

Again, we added an optional polyfill for IE10 and IE11, disabled by default.

Moving on to frontend development, Flex CSS requires a bunch of prefixes for MS browsers, old Firefox versions, Safari and Opera. Invariably, something was always breaking in IE. So we added a small note, fixed on top of the screen, stating that IE is not meant to be supported. It’s our small contribution to web progress.

Challenges

If you are not familiar with WordPress, you should know that it relies heavily on jQuery (an outdated and vulnerable version of it) for all AJAX requests. Our first step was to move to XHR requests, and wrote a nice, tiny wrapper to accommodate it. But then Fetch API came along, and it was (marginally) faster and native. Our theme/plugin has several features which rely on AJAX requests, and using Fetch API would help two-fold: make things faster and remove the jQuery dependency. It took us around two months to refactor all jQuery-dependent code to vanilla JavaScript, but then we got rid of 30-90Kb on every page load (I know that jQuery is cached, but it still needs to be read and interpreted).

Removing jQuery, implementing the Fetch API, removing all browser detection, and using localStorage instead of PHP cookies, made our product 3 to 4 times faster.

More Implementation

As CSS allows us to do more things using siblings, adjacent elements and pseudo selectors, we switched various JavaScript-powered interactions to pure CSS. Styled dropdowns, advanced radiobox-based switches and stylish checkboxes were replaced by CSS. Element transitions and intricate animations (together with easing modes, Bézier curves and custom delays) were replaced by CSS. We also created a basic design system in the process. Well, design system may be too much, it’s a library of elements (forms, buttons, switches, checkboxes, Flex-based columns and more).

Next in the pipeline – maybe early next year – are CSS snap points, <summary> and <details> accordions, autocomplete datalists and WOFF2 custom fonts only, reducing TTI (Time To Interactive) to mere nanoseconds – they add up, you know.

More Speed Improvements

As we work a lot with various layouts and templates, we can’t afford to go old-school with our typography, but I can still ask anybody out there, what’s wrong with Times New Roman? Or using the native system fonts (font-family: -apple-system, BlinkMacSystemFont, Segoe UI, Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif, Segoe UI Symbol, Segoe UI Emoji, Apple Color Emoji;)? Look at GitHub, they’ve been doing it for a while.

Final Thoughts

While working on it, we’ve considered Pjax (but quickly discarded it), page transitions and more AJAXed content. We decided against it, as less JavaScript is always more desirable than actual server-side PHP requests.

Pjax (pushState + AJAX) works by fetching HTML from the server via AJAX and replacing the content of a container element on the page with the loaded HTML. It then updates the current URL in the browser using pushState. This results in faster page navigation for two reasons:

- No page resources (JS, CSS) get re-executed or re-applied.

- If the server is configured for Pjax, it can render only partial page contents and thus avoid the potentially costly full layout render.

We are also keeping an eye on WordPress, which adds more dependencies, more JavaScript and more requests with every iteration. Because of this, we started using ClassicPress with some of our users. I have high hopes from ClassicPress in the next year.

As a conclusion, I am happy to say that we have an almost perfect product, streamlined for our clients’ needs (which are all in the same niche), fast, performant, up-to-date, mobile ready and modern-first with enough graceful degradation on antiquated (or stubborn) browsers.